For centuries, children have utilized various rhymes in playing games, most of which many individuals believe to be farsical in origin or sentences simply designed to facilitate rhythm. Though this may be true in part, like other bits of folklore passed down through 'oral tradition,' an historical 'kernel of truth' often lies at the very foundation of a tale, or in this case, that of a 'jumping rope rhyme.'

Mr. James Smart of Philadelphia often heard his grandmother, Elizabeth Goldsmith Hartley, born in Philadelphia in 1875, repeat the following 'jumping rope rhyme,' which she and other young girls used to recite in their game:

"Gaine's Ghost sat on a Post;

His Feet were full of Blisters.

He made three Grabs at Mary Tabbs

And the Wind blew through his Whiskers."

Mr. Smart and I attempted for a number of years to find any 'historical'' validity behind this curious rhyme. Eventually he was successful, since published newspapers, such as the Evening Bulletin of Philadelphia, for the month of February, 1887, relates all the gruesome details connected with the murder of a Mr.WAITE or WAKEFIELD GAINES, an African-American, whose "headless, legless and armless body" was found "wrapped in coarse brown paper and marked, "Handle with Care," near 'Mann's Millpond,' at Eddington, located near the boundary lines of Bristol and Bensalem Townships, in nearby Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

Eventually, MARY ANN TABBS, a Black woman of Philadelphia, who lived on Richard Street was arrested, a young girl who had repeatedly been seen with Gaines, a waiter by profession, who resided on Schell Street in the city. On one occasion the young woman, with whom the papers described as being "very intimate"with Gaines for some time, but jealous to the extreme, had inflicted a "big cut across his cheek" and was heard cursing him, saying how she "would kill him yet!"

By February 23rd, Miss Tabbs had confessed to the murder, after a number of witnesses had observed her and her peculiar baggage, as she rode on the train from Philadelphia to Eddington. However, she related how Gaines and a Mr. George Wilson, alias George Wallace, had gotten into a fight at her residence, during which Wilson struck Gaines with a "chair stand," by repeated blows, resulting in the latter's death. The body was then dismembered with a cleaver in the cellar, and later distributed 'in pieces,' so Miss Tabbs could handle and discard more easily, the trunk of the corpse.

Wilson, a native of Connecticut, was only nineteen years of age at the time of the murder. Though Miss Tabbs disposed of the 'trunk,' Wilson or Wallace had taken Gaine's "two arms, the two legs and the head" of Gaine's body and "threw them in the Schuylkill River," at the western end of the Callowhill street bridge in Philadelphia.

Though the affidavits or testimony of Tabbs and Wilson would vary, their guilt was established beyond any doubt. The point of this short sketch is to demonstrate the fact, that even something so innocent as a 'jumping rope rhyme,' may at times include historical tidbits, by which history may be re-constructed, confirmed, or verified.

Thus, in doing historical research, be it family, local or national in scope, one should never discount any clue or source as unreliable or of insignificant value, since it has been demonstrated on far too many occasions, that such meagre evidence often may lead one to the proverbial 'pot of gold' for an in-depth and thorough historical reconstruction.

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Monday, November 29, 2010

Little Alma Dora Dustin & the ‘Great Sioux Uprising’ During the American Civil War

Next year, the ‘Sesquicentennial of the American Civil War’ begins in earnest within the United States. Numerous commemoratory events will transpire throughout Pennsylvania and elsewhere, yet few realize that bloodshed, hardship, and even atrocities, were not events experienced only by residents living within the confines of the North and South. Other dramatic & tragic occurrences were transpiring within what is now the state of Minnesota.

For example, in June of 1863, little Alma Dora Dustin, age six, had witnessed it all--and was found by the rescue party alive—days AFTER the event, and though physically uninjured, one wonders of the emotional and psychological scars which may have haunted her throughout her remaining life--- since her mother, father, grandmother, and one brother, lay dead or mangled, tomahawked, scalped or “transfixed” with arrows by their murderers, who incidentally had also ‘cut off her father’s left hand and carried it away,’ as part of a bold, unprovoked attack on an innocent family.

As published by the Annual Report of the Attorney General, to the Legislature of Minnesota, Executive Documents of the State of Minnesota, For the Year 1863, little Alma Dustin:

However, it is almost entirely forgotten in the annals of American history, nor mentioned within college textbooks, though widely reported in the nation’s newspapers at the time (and just a few years ago by Hank H. Cox in, Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862 {Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2005), that one of the greatest massacres of ‘innocent’ civilians occurred in the United States; but not against Native Americans, but upon white civilians by Native-Americans, with the slaughter of over 800 individuals, including numerous women and children. These events would culminate in the deaths of the family of Amos Dustin, in what is now McLeod County, Minnesota, on June 29, 1863, as they made their way by ox-cart to start a new home.

Though the assassins of the Dustin family were never brought to justice, the murders by the Sioux in 1862, resulted in the largest mass hanging in American history. Thirty-nine Native-Americans were executed at Mankato, under the direct order of President Abraham Lincoln, as being responsible for the murders of so many settlers and residents of Minnesota. The names and crimes of the guilty parties were printed for example, within the pages of the Philadelphia Daily Evening Bulletin, for January 2, 1863.

Though many, including myself, have enjoyed Kevin Costner’s highly acclaimed movie, Dances With Wolves, and its Hollywood portrayal of life among the Sioux during the Civil War era, one should always take into account the time-worn truism of the ancient Greek historian, Thucydides, who remarked centuries before Christ that, “Sad to say, most people will believe the first story they hear.”

Human nature has not changed since Thucydides spoke those words so long ago. Most people today still believe to a large degree what they see at the movies, read in a newspaper or scholarly journal, or hear from a professor in a university class, and forget that there are always, two-sides to any given event.

Thus individuals have existed among every race, culture, or ethnic group, who were either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ in their relationships with one another or with outsiders. The early settlers and Native-American Sioux in Minnesota and elsewhere were no different. Thus these comments should not be misconstrued into believing that I feel ALL the Sioux were barbarous murderers. Equally, neither were all colonists, settlers, or military personnel ‘white savages.’ I relate this account in order to give the reader a balance to a subject, which is quite often one-sided in its portrayal of American pioneer history, and our history in general.

My wife and I still cherish the hand-made little moccasin booties, made many years ago, by a dear friend of ours, who happened also to be a female shaman of the Sioux, originally from South Dakota. I have made that tribe’s fascinating history, culture, and folklore, one of my life-long pursuits.

Thus in pursuing historical inquiry, one should be more concerned about accuracy rather than what happens to be academically fashionable or politically correct. To do otherwise, is an injustice to all peoples and cultures. The same is true when it comes to speaking of events which transpired during the Civil War, or any other given time frame within American history.

For example, in June of 1863, little Alma Dora Dustin, age six, had witnessed it all--and was found by the rescue party alive—days AFTER the event, and though physically uninjured, one wonders of the emotional and psychological scars which may have haunted her throughout her remaining life--- since her mother, father, grandmother, and one brother, lay dead or mangled, tomahawked, scalped or “transfixed” with arrows by their murderers, who incidentally had also ‘cut off her father’s left hand and carried it away,’ as part of a bold, unprovoked attack on an innocent family.

As published by the Annual Report of the Attorney General, to the Legislature of Minnesota, Executive Documents of the State of Minnesota, For the Year 1863, little Alma Dustin:

At the commencement of the attack, {she} had crept under the seat occupied by her father, and his blood flowed over her, covering her hands and her face, saturating her hair and her garments to their utmost capacity of absorption, and even filling the shoes on her feet.Writers such as Larry McCurty in his popular work, Oh What a Slaughter: Massacres in the American West: 1846-1890 {NY: Simon & Schuster, 2005), has plenty to say about the well-known and frequently written accounts of atrocities committed against Native-Americans by the military or white settlers, such as the famed ‘Sand Creek & Wounded Knee’ tragedies.

However, it is almost entirely forgotten in the annals of American history, nor mentioned within college textbooks, though widely reported in the nation’s newspapers at the time (and just a few years ago by Hank H. Cox in, Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862 {Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2005), that one of the greatest massacres of ‘innocent’ civilians occurred in the United States; but not against Native Americans, but upon white civilians by Native-Americans, with the slaughter of over 800 individuals, including numerous women and children. These events would culminate in the deaths of the family of Amos Dustin, in what is now McLeod County, Minnesota, on June 29, 1863, as they made their way by ox-cart to start a new home.

Though the assassins of the Dustin family were never brought to justice, the murders by the Sioux in 1862, resulted in the largest mass hanging in American history. Thirty-nine Native-Americans were executed at Mankato, under the direct order of President Abraham Lincoln, as being responsible for the murders of so many settlers and residents of Minnesota. The names and crimes of the guilty parties were printed for example, within the pages of the Philadelphia Daily Evening Bulletin, for January 2, 1863.

Though many, including myself, have enjoyed Kevin Costner’s highly acclaimed movie, Dances With Wolves, and its Hollywood portrayal of life among the Sioux during the Civil War era, one should always take into account the time-worn truism of the ancient Greek historian, Thucydides, who remarked centuries before Christ that, “Sad to say, most people will believe the first story they hear.”

Human nature has not changed since Thucydides spoke those words so long ago. Most people today still believe to a large degree what they see at the movies, read in a newspaper or scholarly journal, or hear from a professor in a university class, and forget that there are always, two-sides to any given event.

Thus individuals have existed among every race, culture, or ethnic group, who were either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ in their relationships with one another or with outsiders. The early settlers and Native-American Sioux in Minnesota and elsewhere were no different. Thus these comments should not be misconstrued into believing that I feel ALL the Sioux were barbarous murderers. Equally, neither were all colonists, settlers, or military personnel ‘white savages.’ I relate this account in order to give the reader a balance to a subject, which is quite often one-sided in its portrayal of American pioneer history, and our history in general.

My wife and I still cherish the hand-made little moccasin booties, made many years ago, by a dear friend of ours, who happened also to be a female shaman of the Sioux, originally from South Dakota. I have made that tribe’s fascinating history, culture, and folklore, one of my life-long pursuits.

Thus in pursuing historical inquiry, one should be more concerned about accuracy rather than what happens to be academically fashionable or politically correct. To do otherwise, is an injustice to all peoples and cultures. The same is true when it comes to speaking of events which transpired during the Civil War, or any other given time frame within American history.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

The 'Other' American Civil War: The Enemy, My Friend?

Next year the country will be celebrating the commemoration of the Sesquicentennial of the American Civil War. Thus, it is only appropriate that today, on Veteran's Day, I relate one of my own favorite military accounts, derived from America's most bloody and violent conflict. Yet the following was an event truly 'civil' in nature; two men, though on opposing sides, quickly but tragically became friends, if only for a short period of time, during the 'Battle of Rome, Georgia,' fought on October 12th, 1864.

A native of Clinton County, Pennsylvania, Lutheran minister, Thomas F. Dornblazer, of Lee County, Illinois, writing within his work, Sabre Strokes of the Pennsylvania Dragoons in the War of 1861-1865, published in Philadelphia in 1884, recalled a remarkable personal incident he experienced during the 'War Between the States.' Dornblazer was serving at the time as a Sergeant, in Company 'E,' 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Minty's Brigade.

One of the opposing 'Rebel' or Confederate forces at Rome, Georgia that fateful day, was the 8th Alabama Cavalry, part of Charles G. Armistead's Brigade. Perhaps it is best to let Sgt. Dornblazer recall his own memories of what transpired (though I have italicized certain words in his reminiscence):

American soldiers, regardless of the conflict, from the Revolutionary War to the current conflict in Afghanistan, have fought valiantly, yet simultaneously have also brought humanitarian aid and shown acts of kindness, to both civilians and enemy combatants alike, so that many of our former enemies, are now our most devoted friends.

As Alexander Pope remarked long ago, "To err is human, to forgive divine."

For further reading, one may wish to read:

Daniel N. Rolph, My Brother's Keeper: Union and Confederate Soldiers' Acts of Mercy During the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books., 2002): 69-71. (for which I hold the copyright)

Thomas F. Dornblazer, Sabre Strokes of the Pennsylvania Dragoons in the War of 1861-65 (Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, 1884): 193-197. Incidentally, Sabre Strokes has been reprinted by a descendant of Dornblazer. Feel free to write me for that author's contact information, as well for further information about my above volume, at: drolph at hsp.org

A native of Clinton County, Pennsylvania, Lutheran minister, Thomas F. Dornblazer, of Lee County, Illinois, writing within his work, Sabre Strokes of the Pennsylvania Dragoons in the War of 1861-1865, published in Philadelphia in 1884, recalled a remarkable personal incident he experienced during the 'War Between the States.' Dornblazer was serving at the time as a Sergeant, in Company 'E,' 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Minty's Brigade.

One of the opposing 'Rebel' or Confederate forces at Rome, Georgia that fateful day, was the 8th Alabama Cavalry, part of Charles G. Armistead's Brigade. Perhaps it is best to let Sgt. Dornblazer recall his own memories of what transpired (though I have italicized certain words in his reminiscence):

After firing a few shots, I saw a Rebel officer leaping the fence twenty yards to my right, and starting to run across the open field to join his comrades. In his right hand he held a navy revolver, and in his left an officer's sword. I leveled my "Spencer" and ordered him, sharply, to halt and throw down his arms, which he did. But seeing that I was altogether alone, he seized his weapons again, sprang to the stump of a broken tree...fired two shots from his revolver, and said in a defiant tone, "I'll fight you!"...

I took my horse by the rein, and made a left about wheel, two paces to the rear...My antagonist in the meantime fired two more shots, wounding my horse in the hip; and mistaking my maneuvers for a retreat, he rushed forward and preemptorily demanded my surrender. He came to the fence...{and} was in the act of stepping across when I ordered him a second time to halt. My gun was leveled; he raised his revolver with a threat: I fired! His arm dropped without discharging his revolver. His tall form sank to the ground as he exclaimed, "I'm a dead man."

At once I dropped my carbine, and offered him my hand; he gave it a friendly grasp and said, "You have killed a good man." "I'm sorry for it," said I, "and why did you take up your arms again?" Said he, "I made a vow that I would never surrender to one man. You were the only man I saw, and I determined to fight you, and get possession of your horse--then I could have made my escape. You did your duty, but you might have surrendered to me."

After making him as comfortable as I could with overcoat and blanket, I inquired his name and rank. He said his name was William H. Lawrence, Captain and acting Colonel of the Eighth Alabama Cavalry. He said he had a wife and two dear children living at Tuscaloosa, Alabama. His wife and daughter were devoted Christians, and he lamented that he had not lived a better life in the army. He did not feel prepared to die. He knew that he must die.

The ball struck the corner of his belt-plate and passed through his body, inflicting a mortal wound. His mind was perfectly clear, anf for one-half hour we were alone, undisturbed, and we wept and prayed together, invoking the Infinite Mercy of God to forgive us both. Seeing the bugler of our regiment at a distance, I called to him to bring up a stretcher to carry back a wounded officer.

We carried him three-quarters of a mile to the field hospital, and had his wounds dressed. Before I left him he gave me his diary, and requested me to send it to his wife, and tell her that he died happy. After his death next day, the surgeon found on his person a ten-dollar gold piece, and a signet-ring with his wife's photograph set in it, in minature.Captain William H. Lawrence, was interred at Myrtle Hill Cemetery, in Rome, Georgia, in the Confederate Soldier's Section. After the War, Dornblazer wrote the Confederate officer's widow, informing her,

That he had in his possession a sword and revolver which belonged to her husband, who fell in battle near Rome, Georgia, and if she desired it, he would forward them to her by express. She said her husband wrote her on the morning of that fatal day, and feared the results of the approaching conflict.

She said her boy "Willie," eleven years old, would like to have his papa's sword. The sword and revolver were forwarded immediately, and a prompt answer came back, with many thanks from the mother and her son.Such at times was the American Civil War. It is not only a subject devoted to 'blood and guts,' heroic actions in battle, atrocities, or animosities between 'Yankees' and 'Rebels.' Oftentimes, as recorded by the very men who served within America's worst national conflict, it was also a time of faith, charity, and brotherly-love, even for those participants whose politics were diametrically in opposition to one another.

American soldiers, regardless of the conflict, from the Revolutionary War to the current conflict in Afghanistan, have fought valiantly, yet simultaneously have also brought humanitarian aid and shown acts of kindness, to both civilians and enemy combatants alike, so that many of our former enemies, are now our most devoted friends.

As Alexander Pope remarked long ago, "To err is human, to forgive divine."

For further reading, one may wish to read:

Daniel N. Rolph, My Brother's Keeper: Union and Confederate Soldiers' Acts of Mercy During the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books., 2002): 69-71. (for which I hold the copyright)

Thomas F. Dornblazer, Sabre Strokes of the Pennsylvania Dragoons in the War of 1861-65 (Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, 1884): 193-197. Incidentally, Sabre Strokes has been reprinted by a descendant of Dornblazer. Feel free to write me for that author's contact information, as well for further information about my above volume, at: drolph at hsp.org

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

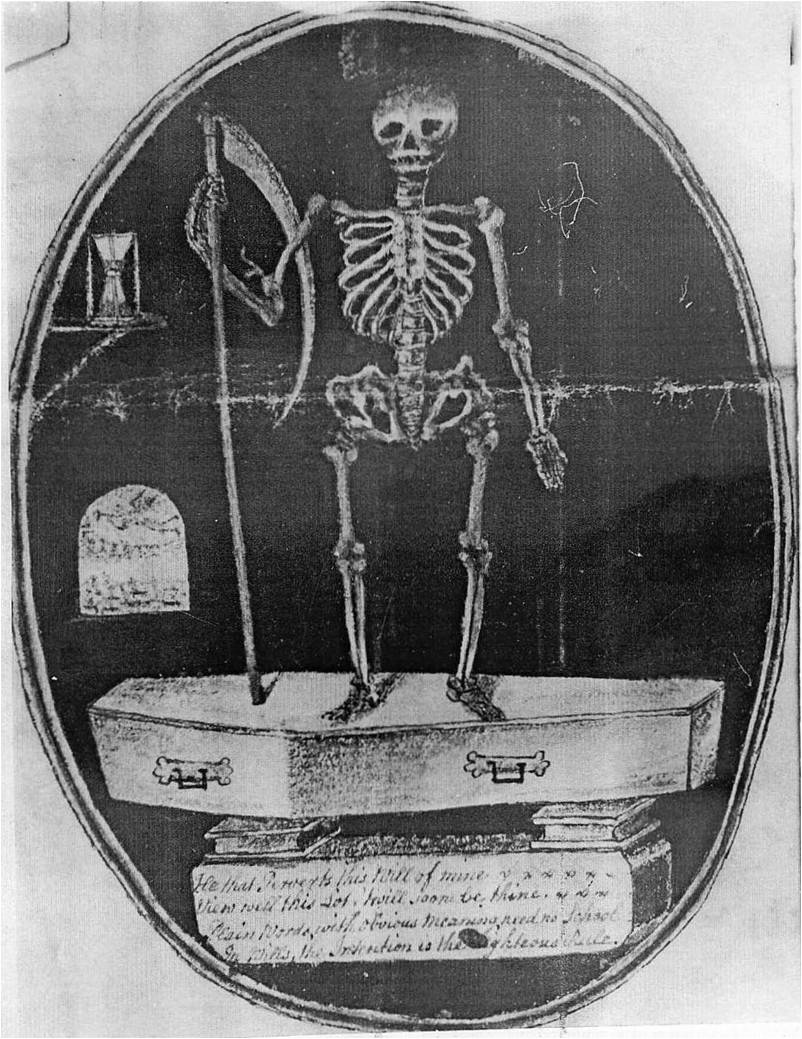

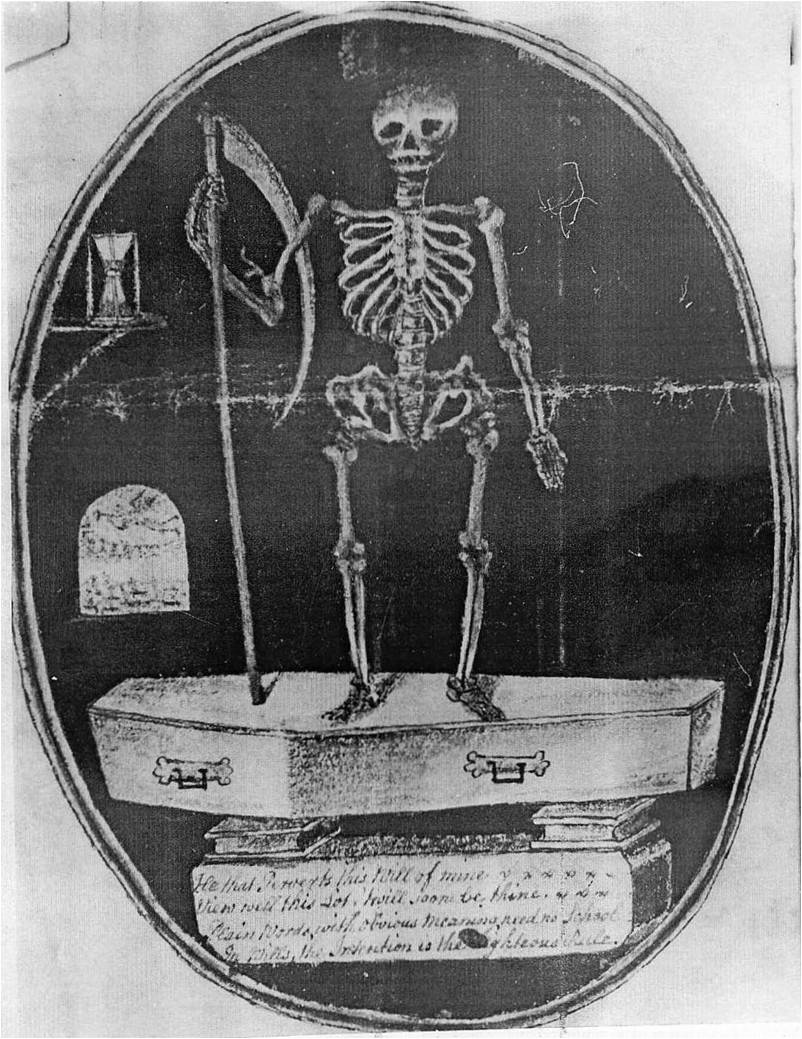

Ghosts in the Library: Haunted Tours of HSP

With Halloween in mind, I will conduct two tours tomorrow of some "haunted" areas of the Historical Society building.

Learn about HSP's resident ghost, Albert, and the spirits in historic garb that have been spotted wandering the stacks of our 100-year-old building. Then come into the vaults yourself for a special tour of these haunted spots...if you dare! $5 for members, $10 for nonmembers. Space is limited.

Learn about HSP's resident ghost, Albert, and the spirits in historic garb that have been spotted wandering the stacks of our 100-year-old building. Then come into the vaults yourself for a special tour of these haunted spots...if you dare! $5 for members, $10 for nonmembers. Space is limited.

Noon and 6 pm Wednesday, October 20 (6 pm slot is sold out)

Learn about HSP's resident ghost, Albert, and the spirits in historic garb that have been spotted wandering the stacks of our 100-year-old building. Then come into the vaults yourself for a special tour of these haunted spots...if you dare! $5 for members, $10 for nonmembers. Space is limited.

Learn about HSP's resident ghost, Albert, and the spirits in historic garb that have been spotted wandering the stacks of our 100-year-old building. Then come into the vaults yourself for a special tour of these haunted spots...if you dare! $5 for members, $10 for nonmembers. Space is limited.To register for this program, click here

Monday, October 18, 2010

A Kiss is Just a Kiss: Or is it? Expensive, dangerous, and even deadly, 'lip-lockings' of past & present

Most everyone is familiar with the lyrics, from the famous song, 'As Time Goes By,' as sung in the movie, Casablanca, which states how, "A Kiss is just a Kiss..." An article in a recent Metro News, for October 15-17, 2010, remarked how "a kiss from the one you love may be exactly what the doctor ordered." That is of course, normally the case.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, for February 18th, 2009, published an article entitled, "The state of the kiss, 2009: Scientifically, historically, emotionally, a smooch says a lot." Actually, so much so, that "A Kiss" at times, "is NOT just a Kiss," contrary to Casablanca song fame. In fact, on many occasions, such examples of affection have proven to be quite deadly perilous in nature, as revealed by the following examples.

A Mr. Birsey, an early inhabitant of Stratford, Fairfield County, Connecticut, during the 17th-century, became a victim of the 'Blue Laws' of that colony, which were strictly enforced, one being that "no man should kiss his wife on Sunday." Living in the community of Milford at the time, Birsey, ignored the edict, but upon the following day, was "sentenced to a number of lashes." However, he escaped the town's authorities, swam across the river and once he stood on the opposite bank at Stratford, he "shook his fists in his pursurers faces."

A famous story is told relative to the French General, the Marquis de la Fayette of Revolutionary fame, who after the 'Battle of Brandywine' in Pennsylvania, was taken to the home of a Dr. Stephens, who resided near Valley Forge, in what is now Chester County. The physician's daughter, Elizabeth, while cleaning her father's upstair's office, encountered Lafayette and one of his young 'aide-de-camps.' The aide, wasting no time in his estimation, quickly "seized the girl and kissed her," after which Lafayette, promptly "turned quickly about and unceremoniously kicked the young gentleman down the steps and out of the house, telling him at the same time that such conduct was not admissable."

Robert Archibald, a young man residing in Philadelphia was arrested in November of 1838, for having "hugged the ladies in the market and attempted to kiss them" as well. The court's decision was that "a man has no right to kiss any lady against her will, excepting his wife, and her he may kiss whether she will or not." Robert's lack of sobriety of course during his 'hugging' and 'kissing' bouts, helped to place him in the Moyamensing Prison for thirty days, until he 'sobered-up.'

'Kissing' could prove to be quite painful at times as well. In October of 1857, a Lexington, Kentucky newspaper article entitled, "Neck Broken in Kissing," related how Catharine Burt was brought to the police station with a "fractured neck," resulting from "a struggle arising from a young man having attempted to kiss her..." No "extra violence" caused the neck injury, but nevertheless, "a partial dislocation of one of the vertebrae of the neck," caused the young woman to have difficulties in swallowing as well as respiration, causing her to lie "in a dangerous state."

Two years later, a Mr. Winder, described as a "young and very handsome public school teacher," from Philadelphia, was driven out of Accomac County, Virginia in August of 1859, "on account of his fondness for kissing his girl pupils." Large or small, it mattered little to the instructor, who is described as chasing the girls, "during school hours...all over the campus." He would "take the girls, when caught, in his arms, and laying their heads on his shoulder passionately kiss them." The young ladies naturally informed their parents who soon dismissed the man from his position of 'education.'

The Philadelphia (PA) Public Ledger, for April 26, 1836, printed an article entitled, "Price of a Smack," relating how a Mr. Mills, of Sandy Hill, New York, was charged and placed on trial for "forcibly taking hold of Mrs. Brayton with the intent to kiss her!" The trial was lengthy, with five jurors in favor of acquittal, and seven desirous to convict the man. Mills finally confessed his guilt, threw himself "upon the mercy of the court; and was fined TWO WHOLE DOLLARS! Thus the price of kissing a lady is legally fixed at two dollars..." The article concluded that since Mrs. Brayton was a "pretty lady," there was no doubt "that the prisoner, if he did kiss her, could well be satisfied with the price fixed by the court, and pay the same cheerfully."

Squire Ben Eggleston of Cincinnati, Ohio in December of 1862, though described as "a venerable gentleman, whose hairs are silvered with the frosts of sixty-five winters," was arraigned in court, in South Covington, Kentucky, "on the charge of kissing Miss Lavina Fenton," contrary to her wishes, described as "a young and beautiful female." The Squire got off cheaply, since he was only fined, "one dollar and costs for the offence."

Kissing one's wife is no guarantee of 'marital bliss,' as was revealed by an account published in the nation's newspapers, during August of 1913, concerning two Philadelphians, Thomas Keen and his wife Etta. The Philadelphia Record related that, "Because his wife refused to kiss him good-bye," he then "shot his wife...in front of her home," but the bullet did not kill her since it was "deflected by her corset." Her husband then swallowed poison, was placed in jail, but later became "violently ill and lapsed into unconsciousness" and died.

In 1861, another woman, age forty, working for a farmer, "aged seventy-five years," residing at Sutton, in Lancashire County, England, received 75 pounds of English currency "for damages sustained in resisting a kiss," which her employer insisted on giving her one evening. During the struggle his female employee "fell over a chair and severely injured her spine." Fast-forward to modern times when in 2008, in the Chinese City of Zhuhai, in southern Guangdong province, a young woman became partially deaf after her boyfriend gave her a passionate kiss, resulting in a ruptured ear drum. The doctors remarked how, "While kissing is normally very safe," they warned that "people should proceed with caution."

An Associated Press article for July of 2001, related a tragic event, when a young Egyptian man, Saber Ahmed Darwish, while on a date with his girl friend, asked her for a kiss, but was refused since he had not proposed to her, though he was only 16 years of age. Darwish, downtrodden after his rejection, "threw himself in the Nile and drowned," leaving as one can imagine, his girlfriend in shock.

A 15-year old girl with an allergic reaction to peanuts, died after her boyfriend kissed her, having just eaten a "peanut butter snack." Christina Desforges died in a Quebec hospital in November of 2005, since doctors were unable to treat her "allergic reaction to the kiss the previous weekend."

Near Tacoma, Washington, in Walla Walla county, in January of 1901, Frank Sloan, "in fun kissed Miss Ella Boone, whom he had blindfolded." Not caring for his advances, the young lady took "a hat pin from her hat," and promptly "stabbed him in the leg." Regrettably, the pin broke and blood poisoning occurred. Though Sloan went to the hospital for an X-ray the following day, because of the intense pain, he soon grew physically worse and actually died. According to the article, published in the Philadelphia (PA) Public Ledger, Miss Boone had mentioned in the presence of Sloan how 'she'd never been kissed.' But this "innocent remark led to Sloan's death."

Thus one can see that a so-called 'simple kiss,' can be much more complex, dangerous, and expensive, but also humorous as well at times. The Lebanon (PA) Daily News, for August 30, 1881 lamented the fact that "a man kissed a woman up in Wisconsin. She had half the fun and did not do any work and yet she wanted pay for it. The jury gave her $600."

The above article goes on to remark how, "There are hundreds of girls in Arkansas with mouths nine inches long, and you can commence at one end and kiss clear around to the other; and then you can go back over the trail and kiss, and kiss, and kiss, and kiss till your lips blister and you have extracted sweetness enough to make a barrel of molasses and she won't charge you a cent for it! But then Arkansas is nine hundred years ahead of the rest of the world."

What more can be said!

The Philadelphia Inquirer, for February 18th, 2009, published an article entitled, "The state of the kiss, 2009: Scientifically, historically, emotionally, a smooch says a lot." Actually, so much so, that "A Kiss" at times, "is NOT just a Kiss," contrary to Casablanca song fame. In fact, on many occasions, such examples of affection have proven to be quite deadly perilous in nature, as revealed by the following examples.

A Mr. Birsey, an early inhabitant of Stratford, Fairfield County, Connecticut, during the 17th-century, became a victim of the 'Blue Laws' of that colony, which were strictly enforced, one being that "no man should kiss his wife on Sunday." Living in the community of Milford at the time, Birsey, ignored the edict, but upon the following day, was "sentenced to a number of lashes." However, he escaped the town's authorities, swam across the river and once he stood on the opposite bank at Stratford, he "shook his fists in his pursurers faces."

A famous story is told relative to the French General, the Marquis de la Fayette of Revolutionary fame, who after the 'Battle of Brandywine' in Pennsylvania, was taken to the home of a Dr. Stephens, who resided near Valley Forge, in what is now Chester County. The physician's daughter, Elizabeth, while cleaning her father's upstair's office, encountered Lafayette and one of his young 'aide-de-camps.' The aide, wasting no time in his estimation, quickly "seized the girl and kissed her," after which Lafayette, promptly "turned quickly about and unceremoniously kicked the young gentleman down the steps and out of the house, telling him at the same time that such conduct was not admissable."

Robert Archibald, a young man residing in Philadelphia was arrested in November of 1838, for having "hugged the ladies in the market and attempted to kiss them" as well. The court's decision was that "a man has no right to kiss any lady against her will, excepting his wife, and her he may kiss whether she will or not." Robert's lack of sobriety of course during his 'hugging' and 'kissing' bouts, helped to place him in the Moyamensing Prison for thirty days, until he 'sobered-up.'

'Kissing' could prove to be quite painful at times as well. In October of 1857, a Lexington, Kentucky newspaper article entitled, "Neck Broken in Kissing," related how Catharine Burt was brought to the police station with a "fractured neck," resulting from "a struggle arising from a young man having attempted to kiss her..." No "extra violence" caused the neck injury, but nevertheless, "a partial dislocation of one of the vertebrae of the neck," caused the young woman to have difficulties in swallowing as well as respiration, causing her to lie "in a dangerous state."

Two years later, a Mr. Winder, described as a "young and very handsome public school teacher," from Philadelphia, was driven out of Accomac County, Virginia in August of 1859, "on account of his fondness for kissing his girl pupils." Large or small, it mattered little to the instructor, who is described as chasing the girls, "during school hours...all over the campus." He would "take the girls, when caught, in his arms, and laying their heads on his shoulder passionately kiss them." The young ladies naturally informed their parents who soon dismissed the man from his position of 'education.'

The Philadelphia (PA) Public Ledger, for April 26, 1836, printed an article entitled, "Price of a Smack," relating how a Mr. Mills, of Sandy Hill, New York, was charged and placed on trial for "forcibly taking hold of Mrs. Brayton with the intent to kiss her!" The trial was lengthy, with five jurors in favor of acquittal, and seven desirous to convict the man. Mills finally confessed his guilt, threw himself "upon the mercy of the court; and was fined TWO WHOLE DOLLARS! Thus the price of kissing a lady is legally fixed at two dollars..." The article concluded that since Mrs. Brayton was a "pretty lady," there was no doubt "that the prisoner, if he did kiss her, could well be satisfied with the price fixed by the court, and pay the same cheerfully."

Squire Ben Eggleston of Cincinnati, Ohio in December of 1862, though described as "a venerable gentleman, whose hairs are silvered with the frosts of sixty-five winters," was arraigned in court, in South Covington, Kentucky, "on the charge of kissing Miss Lavina Fenton," contrary to her wishes, described as "a young and beautiful female." The Squire got off cheaply, since he was only fined, "one dollar and costs for the offence."

Kissing one's wife is no guarantee of 'marital bliss,' as was revealed by an account published in the nation's newspapers, during August of 1913, concerning two Philadelphians, Thomas Keen and his wife Etta. The Philadelphia Record related that, "Because his wife refused to kiss him good-bye," he then "shot his wife...in front of her home," but the bullet did not kill her since it was "deflected by her corset." Her husband then swallowed poison, was placed in jail, but later became "violently ill and lapsed into unconsciousness" and died.

In 1861, another woman, age forty, working for a farmer, "aged seventy-five years," residing at Sutton, in Lancashire County, England, received 75 pounds of English currency "for damages sustained in resisting a kiss," which her employer insisted on giving her one evening. During the struggle his female employee "fell over a chair and severely injured her spine." Fast-forward to modern times when in 2008, in the Chinese City of Zhuhai, in southern Guangdong province, a young woman became partially deaf after her boyfriend gave her a passionate kiss, resulting in a ruptured ear drum. The doctors remarked how, "While kissing is normally very safe," they warned that "people should proceed with caution."

An Associated Press article for July of 2001, related a tragic event, when a young Egyptian man, Saber Ahmed Darwish, while on a date with his girl friend, asked her for a kiss, but was refused since he had not proposed to her, though he was only 16 years of age. Darwish, downtrodden after his rejection, "threw himself in the Nile and drowned," leaving as one can imagine, his girlfriend in shock.

A 15-year old girl with an allergic reaction to peanuts, died after her boyfriend kissed her, having just eaten a "peanut butter snack." Christina Desforges died in a Quebec hospital in November of 2005, since doctors were unable to treat her "allergic reaction to the kiss the previous weekend."

Near Tacoma, Washington, in Walla Walla county, in January of 1901, Frank Sloan, "in fun kissed Miss Ella Boone, whom he had blindfolded." Not caring for his advances, the young lady took "a hat pin from her hat," and promptly "stabbed him in the leg." Regrettably, the pin broke and blood poisoning occurred. Though Sloan went to the hospital for an X-ray the following day, because of the intense pain, he soon grew physically worse and actually died. According to the article, published in the Philadelphia (PA) Public Ledger, Miss Boone had mentioned in the presence of Sloan how 'she'd never been kissed.' But this "innocent remark led to Sloan's death."

Thus one can see that a so-called 'simple kiss,' can be much more complex, dangerous, and expensive, but also humorous as well at times. The Lebanon (PA) Daily News, for August 30, 1881 lamented the fact that "a man kissed a woman up in Wisconsin. She had half the fun and did not do any work and yet she wanted pay for it. The jury gave her $600."

The above article goes on to remark how, "There are hundreds of girls in Arkansas with mouths nine inches long, and you can commence at one end and kiss clear around to the other; and then you can go back over the trail and kiss, and kiss, and kiss, and kiss till your lips blister and you have extracted sweetness enough to make a barrel of molasses and she won't charge you a cent for it! But then Arkansas is nine hundred years ahead of the rest of the world."

What more can be said!

Two Hispanic Brothers and Soldiers

This article appeared in the free monthly HSP Newsletter, History Hits.

***

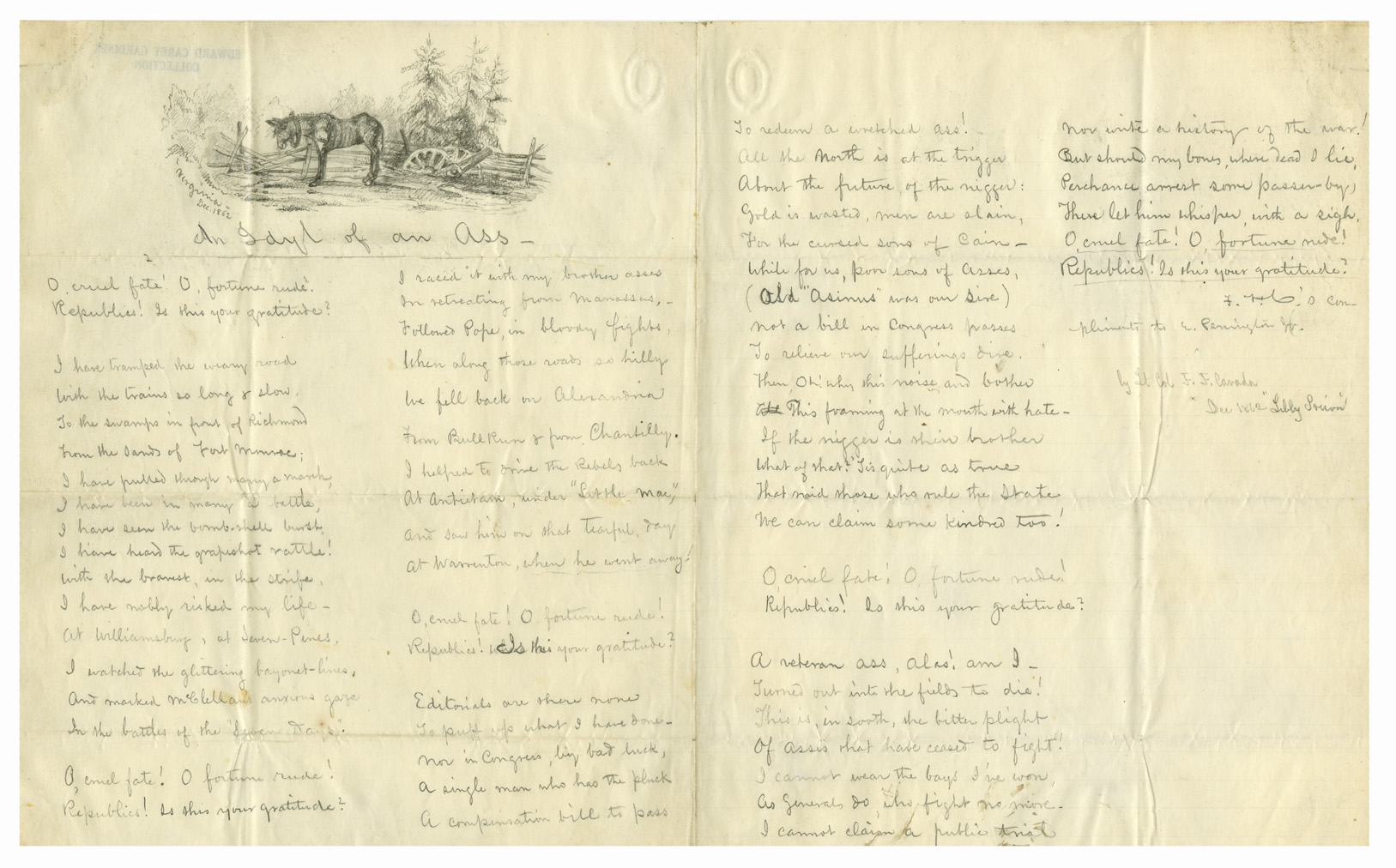

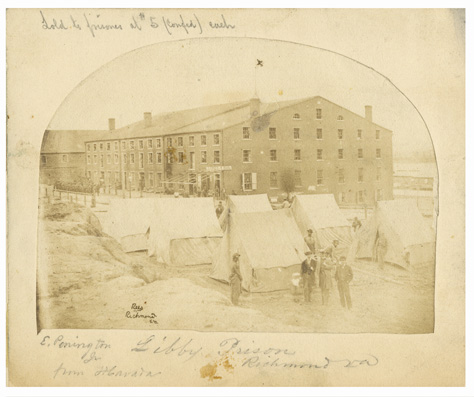

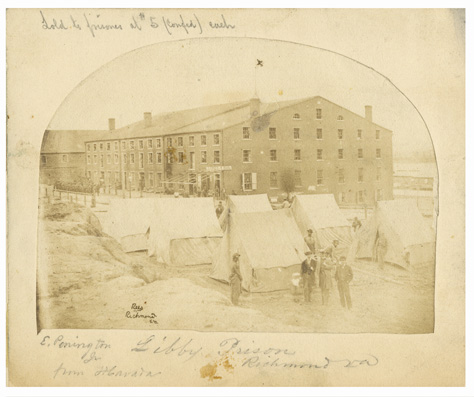

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Adolph and Frederick willingly enlisted in the Federal forces, serving as captains of various companies in the Philadelphia 23rd PA Infantry Regiment. Adolph served with distinction in the Army of the Potomac from Fredericksburg to Gettysburg and was a "special aide-de-camp" to General Andrew Humphries. Frederick transferred to the 114th PA Infantry Regiment, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Frederick gained notoriety as well from his writings, sketches, and paintings related to his incarceration as a prisoner-of-war in the infamous Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia (pictured at right). Below is a poem written by Cavada in 1862. He writes: "I have pulled through many a march, I have been in many a battle, I have seen the bomb-shell burst, I have heard the grapeshot rattle! With the bravest, in the strife, I have nobly risked my life."

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Adolph and Frederick willingly enlisted in the Federal forces, serving as captains of various companies in the Philadelphia 23rd PA Infantry Regiment. Adolph served with distinction in the Army of the Potomac from Fredericksburg to Gettysburg and was a "special aide-de-camp" to General Andrew Humphries. Frederick transferred to the 114th PA Infantry Regiment, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Frederick gained notoriety as well from his writings, sketches, and paintings related to his incarceration as a prisoner-of-war in the infamous Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia (pictured at right). Below is a poem written by Cavada in 1862. He writes: "I have pulled through many a march, I have been in many a battle, I have seen the bomb-shell burst, I have heard the grapeshot rattle! With the bravest, in the strife, I have nobly risked my life."  Though raised in Philadelphia, both brothers continued to maintain a strong connection to their native isle of Cuba. After the American Civil War, the Federal government appointed the brothers to Consular positions--Frederick in Trinidad and Adolph in Cienfuegos.

Though raised in Philadelphia, both brothers continued to maintain a strong connection to their native isle of Cuba. After the American Civil War, the Federal government appointed the brothers to Consular positions--Frederick in Trinidad and Adolph in Cienfuegos.

***

Adolph (Adolfo) Fernandez Cavada and Frederick (Federico) Fernandez Cavada were born in Cienfuegos, Cuba, sons of a Cuban father and Emily Howard, a native of Philadelphia. When their father died, the boys and their mother moved to Pennsylvania. They were educated in private schools and graduated from Central High School.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Adolph and Frederick willingly enlisted in the Federal forces, serving as captains of various companies in the Philadelphia 23rd PA Infantry Regiment. Adolph served with distinction in the Army of the Potomac from Fredericksburg to Gettysburg and was a "special aide-de-camp" to General Andrew Humphries. Frederick transferred to the 114th PA Infantry Regiment, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Frederick gained notoriety as well from his writings, sketches, and paintings related to his incarceration as a prisoner-of-war in the infamous Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia (pictured at right). Below is a poem written by Cavada in 1862. He writes: "I have pulled through many a march, I have been in many a battle, I have seen the bomb-shell burst, I have heard the grapeshot rattle! With the bravest, in the strife, I have nobly risked my life."

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Adolph and Frederick willingly enlisted in the Federal forces, serving as captains of various companies in the Philadelphia 23rd PA Infantry Regiment. Adolph served with distinction in the Army of the Potomac from Fredericksburg to Gettysburg and was a "special aide-de-camp" to General Andrew Humphries. Frederick transferred to the 114th PA Infantry Regiment, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Frederick gained notoriety as well from his writings, sketches, and paintings related to his incarceration as a prisoner-of-war in the infamous Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia (pictured at right). Below is a poem written by Cavada in 1862. He writes: "I have pulled through many a march, I have been in many a battle, I have seen the bomb-shell burst, I have heard the grapeshot rattle! With the bravest, in the strife, I have nobly risked my life." One of the most vivid and articulate accounts of the Battle of Gettysburg comes from the pen of Adolph, who kept a diary during the war (pictured below). His eye-witness experience of the famous conflict provides a highly descriptive and informative rendition of the heroism, horror, and sounds of battle. During one of the days during the July battle, he recorded how "The air was soon full of flying shot, shell and canister--and a groan here and there attested their affect. ...the roar of musketry and the crashing, pounding noise of guns and bursting shells was deafening... "

Though raised in Philadelphia, both brothers continued to maintain a strong connection to their native isle of Cuba. After the American Civil War, the Federal government appointed the brothers to Consular positions--Frederick in Trinidad and Adolph in Cienfuegos.

Though raised in Philadelphia, both brothers continued to maintain a strong connection to their native isle of Cuba. After the American Civil War, the Federal government appointed the brothers to Consular positions--Frederick in Trinidad and Adolph in Cienfuegos. During the War of Cuban Independence, which broke out in 1868, the two brothers resigned from their commissions and became acutely involved in the Cuban Army of Liberation from Spain. Both became officers in the uprising, with Frederick becoming the commander in chief of all Cuban revolutionary forces. Both brothers lost their lives during the fight for Cuban independence.

Frederick, called the "Fire King" by the Spanish authorities during the above struggle, was captured, court-martialed, and sentenced, with the rumor he was to be hanged. Many of his former friends and military compatriots with whom he'd served with in the Union Army--including Generals George Gordon Meade, Daniel Sickles, and Ulysses S. Grant--attempted to obtain his release without success.

Sometime during the month of July in 1871, Frederick Cavada was taken to Puerto Principe and executed. During the hour of his death, it was reported that Cavada calmly "conversed with some friends," smoked a cigar, and walked "erect and proud to the place of execution" where he flung his hat to the ground "and in a loud tone of voice cried, 'Adios Cuba, para siempre' (Goodbye Cuba, forever)." After this a volley was fired and Cavada was killed.

The Cavada brothers, natives of Cuba and residents of Philadelphia, fought for both their adopted and native lands. Their story attests to the patriotic heritage that is a significant part of not only one family, but of the Hispanic community as a whole.

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Shaking Hands: An Ancient & Early American Custom

The origin of two individuals shaking hands, as a sign of friendship, legal commitment or oath-taking, is lost in antiquity, though examples of it exist in both stone and illustration as far back as the 5th century B.C., in early Greece.

In our own nation, not many years ago, a handshake was once as binding as a verbal or written agreement, at least before the plethora of lawsuits became the norm in our society. 'A Man's Word is his Bond,' was a common phrase in early Colonial and pioneer days, and though still used in present-day vernacular, regrettably, no private or public institution, nor sane person would consider it legally binding in today's world.

Thus reams of paper with signatures signed in triplicate, along with a multitude of fees paid, are now considered the norm in any contractual agreement. The handshake has been relegated to that of a quaint custom, rather than an act of solemnity and serious dedication.

But this was not always the situation, as is revealed by an early court case, handled by the famous founder of Philadelphia and early Pennsylvania colony, the country's most famous Quaker, that of William Penn.

While William Penn was serving as both Proprietor and Governor in Colonial Pennsylvania, his Council met on May 13, 1684 to discuss a disagreement between two early Swedish inhabitants, Andrew Johnson and Hans or Hance Peterson. The court case reads simply as follows:

However, it is the final sentence of the case which gives added 'weight' to the validity and binding nature of this custom and incident, since it states: "It was also Ordered that the Records of the Court Concerning that Business should be burnt."

The above account IS the case. The original court record does not survive in any other form, except as recorded as above, which was later printed within the Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, Vol.1 (Harrisburg, PA: 1838): 52.

In the next century, during the Revolutionary War, a Captain Thomas B. Bowen of the Ninth Pennsylvania Regiment, was renown for his hot temper and on occasion would challenge his offender to a duel. These conflicts became quite common in 19th-century America, although the last duel in Pennsylvania resulted in the death of Tarleton Bates, on January 8, 1806 in Allegheny County at Pittsburgh.

A Captain Bower in Bowen's regiment made an unintended snide remark to the latter, while he was playing backgammon with Charles Biddle, another famous Pennsylvanian. Bower apologized, but Captain Bowen asked Biddle if he should 'challenge' the man to a duel. Biddle wisely replied:

In our own nation, not many years ago, a handshake was once as binding as a verbal or written agreement, at least before the plethora of lawsuits became the norm in our society. 'A Man's Word is his Bond,' was a common phrase in early Colonial and pioneer days, and though still used in present-day vernacular, regrettably, no private or public institution, nor sane person would consider it legally binding in today's world.

Thus reams of paper with signatures signed in triplicate, along with a multitude of fees paid, are now considered the norm in any contractual agreement. The handshake has been relegated to that of a quaint custom, rather than an act of solemnity and serious dedication.

But this was not always the situation, as is revealed by an early court case, handled by the famous founder of Philadelphia and early Pennsylvania colony, the country's most famous Quaker, that of William Penn.

While William Penn was serving as both Proprietor and Governor in Colonial Pennsylvania, his Council met on May 13, 1684 to discuss a disagreement between two early Swedish inhabitants, Andrew Johnson and Hans or Hance Peterson. The court case reads simply as follows:

"There being a Difference depending between them, the Governor & Councill advised them to shake hands, and to forgive One another; and Ordered that they should Enter in Bonds for fifty pounds apiece, for their good abearance; which accordingly they did."It is thus normal to assume that the two men naturally agreed to the contract since they were required to both pay a bond or fee, in order to seal the bargain.

However, it is the final sentence of the case which gives added 'weight' to the validity and binding nature of this custom and incident, since it states: "It was also Ordered that the Records of the Court Concerning that Business should be burnt."

The above account IS the case. The original court record does not survive in any other form, except as recorded as above, which was later printed within the Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, Vol.1 (Harrisburg, PA: 1838): 52.

In the next century, during the Revolutionary War, a Captain Thomas B. Bowen of the Ninth Pennsylvania Regiment, was renown for his hot temper and on occasion would challenge his offender to a duel. These conflicts became quite common in 19th-century America, although the last duel in Pennsylvania resulted in the death of Tarleton Bates, on January 8, 1806 in Allegheny County at Pittsburgh.

A Captain Bower in Bowen's regiment made an unintended snide remark to the latter, while he was playing backgammon with Charles Biddle, another famous Pennsylvanian. Bower apologized, but Captain Bowen asked Biddle if he should 'challenge' the man to a duel. Biddle wisely replied:

"A man who would not fight on some occasions was not fit to live, nor was a man fit to live who was always quarreling." Biddle had both men shake hands and thus a duel was avoided.One wonders how peaceful our nation and world-at-large would be, if only a simple handshake could bring about peace and serve as a deterrent to conflict as it once did on many occasions. Yes, a handshake may be considered once again a quaint & old-fashioned custom in today's so-called sophisticated world. But then again, maybe it would be wise in many cases to 're-invent the wheel.'

Friday, August 27, 2010

Hydrophobia and Mad Dog Bites in Philadelphia

This article appeared in the free monthly HSP Newsletter, History Hits. Click here to subscribe.

***

Philadelphia newspapers, particularly for the 18th and 19th centuries, are filled with accounts of individuals unfortunate enough to be bitten by rabid dogs. The dog bites led to the dreaded disease known as hydrophobia, an often fatal malady.

On May 5, 1811, Roberts Vaux wrote to Robert L. Pitfield concerning the “Mad Dog Scare in Philadelphia.” Dogs in the city were required to wear collars in order “to prevent their biting the citizens.” In the previous century, Dr. Benjamin Rush had spent a considerable amount of time corresponding with other physicians, asking for their suggested remedies to cure victims of mad dog bites. Treatments at the time included multiple bleedings and “pouring cold water on the bitten part & heads of victims.”

A curious advertisement appeared in Benjamin Franklin’s famed Pennsylvania Gazette on April 7, 1779, in which Daniel Goodman (by profession a baker) claimed that he had been able to cure the “BITE of a MAD DOG” for years, as many in Philadelphia could attest, and added that:

“My ancestors, for upwards of 150 years, did successfully practice the same cure in Old England, when the ablest of physicians there…have failed therein.”

Beginning in 1818, the Philadelphia City Directories list a Mary Goodman (widow of Samuel Goodman) who “cures the bites of mad animals.” Goodman resided at 12 Kunckel Street or Kunkle, now Dillwyn, located in the Northern Liberties section of the city. She continued to pursue this occupation for a number of years until she was simply listed as a “gentlew,” short for “Gentlewoman,” implying a certain amount of wealth or property.

Mary Goodman died on Monday evening, October 25, 1830. Her obituary, which appeared in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, simply states that she was “age 75 years,” and that her funeral would be held at her Kunckle Street residence “to which her friends are invited.”

What exactly was the “Goodman cure” for hydrophobia? It is never actually described; however, one can assume it might have been what is referred to as a mad stone. This stone was a curious substance that was heated, applied to the wound, and thought to absorb poison from the victim.

The correspondence of Dr. Benjamin Rush includes a letter from Dr. Samuel Davies of Petersburg, Virginia, who in 1801 relates to Rush an account of one such stone used in Matthews County. Davies stated that: “…the stone was put in warm water, wiped-applied to the lower wound, which it was secured by a tight bandage for 12 hours, then taken off…on its being put into the warm water after the first application, there issued from one corner of the stone a stream of bubbles which the owner told me was the poison…”

Such tantalizing information reveals the medical practices and beliefs of an earlier generation.

***

|

| Advertisement of Daniel Goodman |

On May 5, 1811, Roberts Vaux wrote to Robert L. Pitfield concerning the “Mad Dog Scare in Philadelphia.” Dogs in the city were required to wear collars in order “to prevent their biting the citizens.” In the previous century, Dr. Benjamin Rush had spent a considerable amount of time corresponding with other physicians, asking for their suggested remedies to cure victims of mad dog bites. Treatments at the time included multiple bleedings and “pouring cold water on the bitten part & heads of victims.”

A curious advertisement appeared in Benjamin Franklin’s famed Pennsylvania Gazette on April 7, 1779, in which Daniel Goodman (by profession a baker) claimed that he had been able to cure the “BITE of a MAD DOG” for years, as many in Philadelphia could attest, and added that:

“My ancestors, for upwards of 150 years, did successfully practice the same cure in Old England, when the ablest of physicians there…have failed therein.”

|

| City Directory |

Beginning in 1818, the Philadelphia City Directories list a Mary Goodman (widow of Samuel Goodman) who “cures the bites of mad animals.” Goodman resided at 12 Kunckel Street or Kunkle, now Dillwyn, located in the Northern Liberties section of the city. She continued to pursue this occupation for a number of years until she was simply listed as a “gentlew,” short for “Gentlewoman,” implying a certain amount of wealth or property.

Mary Goodman died on Monday evening, October 25, 1830. Her obituary, which appeared in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, simply states that she was “age 75 years,” and that her funeral would be held at her Kunckle Street residence “to which her friends are invited.”

What exactly was the “Goodman cure” for hydrophobia? It is never actually described; however, one can assume it might have been what is referred to as a mad stone. This stone was a curious substance that was heated, applied to the wound, and thought to absorb poison from the victim.

|

| Letter of Dr. Samuel Davies to Dr. Benjamin Rush, for 1801 |

Such tantalizing information reveals the medical practices and beliefs of an earlier generation.

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

Mines: Mysterious Discoveries and Miracles?

As I write these words, an attempt is being made to rescue thirty-three trapped miners, deep inside the San Jose gold and copper mine at Copiapo in the country of Chile. Plus, August 27 is the 47th anniversary of one of the most famous mining disasters and rescue operations to have occurred in Pennsylvania, which captured both the country and the world's attention, of which I'll shortly return and give a brief account.

Mines, and the subterranean world in general, have for centuries entered the realm of legend, myth, folklore, as well as history, as repositories of the unknown. Well-known accounts range from the Lost Dutchman Gold Mine of the Superstition Mountains near Phoenix, Arizona, to totally fictional novels like those of Jules Verne's famed 19th-century work, Journey to the Center of the Earth, to Stanton A. Coblentz' Hidden World, first published in 1935. Such stories have continued to capture the public's imagination.

But mines can truly be strange places indeed, as revealed by numerous large 'dinosaur tracks,' discovered for years and removed from the roofs of coal mines in central Utah, to that of the 'perpetual fire' that has continued to burn since 1962, in a strip mine underneath Centralia, Columbia County, Pennsylvania, within the state's anthracite coal region.

Mining excavations carried out in northern Italy, from 1871-1958, have uncovered some fifty individual skeletons of a primitive ape-like creature, referred to as Oreopithecus bambolii or the 'swamp or hill ape.' However, perhaps the most bizarre discovery was recorded in Latin as long ago as the 15th century, by the Italian writer Baptista Fulgosus. He relates the discovery by miners, in the year 1460, while digging within a 'metal ore mine' at Berne, Switzerland, high in the Alps, at some 50 fathoms or 300 feet beneath the earth, of an entire ship, 'with anchors of rusted iron, broken masts, shredded linen sails and the carcasses of some 48 men!' As Fulgosus himself states, this excavation was carried out within 'his own time,' and that the arti-factual and human remains were seen by "many grave and sober men," from whom he "received a personal account of it."

Which brings us to the events on August 13,1963, at Sheppton, located in the anthracite coal belt of Schuylkill County in eastern Pennsylvania where the famed Sheppton Mine Disaster and Rescue transpired. Three men were trapped some 330 feet beneath the earth after the collapse of a mining shaft. Some two weeks later, on Tuesday, August 27th, two of the miners, Henry Throne and David Fellin, were brought safely to the surface, after rescuers successfully drilled a 17 1/2-inch and later 28-inch borehole into their chamber, while the third miner, Lou Bova, being trapped in another part of the mine, regrettably perished.

The story of Throne and Fellin's survival and rescue were enough to captivate the world's attention, but it was what they claimed they saw and heard, while entombed, that fascinated the public, statements which both men swore as to their authenticity, both separately and publicly, emphatic declarations which they took to their graves, though others believed they had simultaneously witnessed the same hallucinations.

David Fellin's 'affidavit' was printed in the Philadelphia Inquirer on August 29, 1963, wherein he remarked how, "Now they're trying to tell me those things were hallucinations, that we imagined it all. We didn't. Our minds weren't playing tricks on us. I've been a practical, hard-headed coal miner all my life. My mind was clear down there in the mine. It's still clear."

Fellin went on to remark, how some of the things he and Throne saw, they couldn't explain in words, while on the other hand, he stated that, "On the fourth or fifth day, we saw this door although we had no light from above or from our helmets. The door was covered in bright blue light. It was very clear, better than sunlight. Two ordinary looking men, not miners, opened the door. We could see beautiful marble steps on the other side. We saw this for some time and then we didn't see it..We saw many other things like that that you couldn't explain. But I'm not going to tell you about them because I feel too deeply about all this."

Both men would also claim that they were visited by Pope John XXIII, who had died some ten weeks previously, prior to the mining disaster, and that the deceased pontiff had in reality stayed with them a full eight days!

Whether one wishes to believe the above statements in regard to artifacts discovered within mines over time, or the above statements by the late David Fellin as miracles or hallucinations is not my concern. I simply share with you some of the strange things that are connected with mines and mining disasters, some of which have transpired here in Pennsylvania, partly available here at The Historical Society of Pennsylvania as part of its varied collection.

*For further information relative to the Sheppton Mine Rescue, one can consult the following:

James A. Goodman, Two Weeks Under: The Sheppton Mine Disaster/Miracle (Coal Hole Productions, March 2004)

J. Ronnie Sando, The Famous Sheppton Mine Rescue: The Untold Story: The Blood and Sweat of the Rescue Team (Publish America, July 16th, 2007).

"Rescued Miners Tell Own Stories of 14-Day Ordeal." Philadelphia Inquirer, August 29th, 1963, p.3.

Mines, and the subterranean world in general, have for centuries entered the realm of legend, myth, folklore, as well as history, as repositories of the unknown. Well-known accounts range from the Lost Dutchman Gold Mine of the Superstition Mountains near Phoenix, Arizona, to totally fictional novels like those of Jules Verne's famed 19th-century work, Journey to the Center of the Earth, to Stanton A. Coblentz' Hidden World, first published in 1935. Such stories have continued to capture the public's imagination.

But mines can truly be strange places indeed, as revealed by numerous large 'dinosaur tracks,' discovered for years and removed from the roofs of coal mines in central Utah, to that of the 'perpetual fire' that has continued to burn since 1962, in a strip mine underneath Centralia, Columbia County, Pennsylvania, within the state's anthracite coal region.

Mining excavations carried out in northern Italy, from 1871-1958, have uncovered some fifty individual skeletons of a primitive ape-like creature, referred to as Oreopithecus bambolii or the 'swamp or hill ape.' However, perhaps the most bizarre discovery was recorded in Latin as long ago as the 15th century, by the Italian writer Baptista Fulgosus. He relates the discovery by miners, in the year 1460, while digging within a 'metal ore mine' at Berne, Switzerland, high in the Alps, at some 50 fathoms or 300 feet beneath the earth, of an entire ship, 'with anchors of rusted iron, broken masts, shredded linen sails and the carcasses of some 48 men!' As Fulgosus himself states, this excavation was carried out within 'his own time,' and that the arti-factual and human remains were seen by "many grave and sober men," from whom he "received a personal account of it."

Which brings us to the events on August 13,1963, at Sheppton, located in the anthracite coal belt of Schuylkill County in eastern Pennsylvania where the famed Sheppton Mine Disaster and Rescue transpired. Three men were trapped some 330 feet beneath the earth after the collapse of a mining shaft. Some two weeks later, on Tuesday, August 27th, two of the miners, Henry Throne and David Fellin, were brought safely to the surface, after rescuers successfully drilled a 17 1/2-inch and later 28-inch borehole into their chamber, while the third miner, Lou Bova, being trapped in another part of the mine, regrettably perished.

The story of Throne and Fellin's survival and rescue were enough to captivate the world's attention, but it was what they claimed they saw and heard, while entombed, that fascinated the public, statements which both men swore as to their authenticity, both separately and publicly, emphatic declarations which they took to their graves, though others believed they had simultaneously witnessed the same hallucinations.

David Fellin's 'affidavit' was printed in the Philadelphia Inquirer on August 29, 1963, wherein he remarked how, "Now they're trying to tell me those things were hallucinations, that we imagined it all. We didn't. Our minds weren't playing tricks on us. I've been a practical, hard-headed coal miner all my life. My mind was clear down there in the mine. It's still clear."

Fellin went on to remark, how some of the things he and Throne saw, they couldn't explain in words, while on the other hand, he stated that, "On the fourth or fifth day, we saw this door although we had no light from above or from our helmets. The door was covered in bright blue light. It was very clear, better than sunlight. Two ordinary looking men, not miners, opened the door. We could see beautiful marble steps on the other side. We saw this for some time and then we didn't see it..We saw many other things like that that you couldn't explain. But I'm not going to tell you about them because I feel too deeply about all this."

Both men would also claim that they were visited by Pope John XXIII, who had died some ten weeks previously, prior to the mining disaster, and that the deceased pontiff had in reality stayed with them a full eight days!

Whether one wishes to believe the above statements in regard to artifacts discovered within mines over time, or the above statements by the late David Fellin as miracles or hallucinations is not my concern. I simply share with you some of the strange things that are connected with mines and mining disasters, some of which have transpired here in Pennsylvania, partly available here at The Historical Society of Pennsylvania as part of its varied collection.

*For further information relative to the Sheppton Mine Rescue, one can consult the following:

James A. Goodman, Two Weeks Under: The Sheppton Mine Disaster/Miracle (Coal Hole Productions, March 2004)

J. Ronnie Sando, The Famous Sheppton Mine Rescue: The Untold Story: The Blood and Sweat of the Rescue Team (Publish America, July 16th, 2007).

"Rescued Miners Tell Own Stories of 14-Day Ordeal." Philadelphia Inquirer, August 29th, 1963, p.3.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Antarctica: The Lost Continent

As a follow-up to my recent post on Antarctica, I wanted to add this article which appeared in the free monthly HSP Newsletter, History Hits. Click here to subscribe.

***

During the middle of the summer heat, we thought we’d focus on one of the coldest places on earth—the continent of Antarctica. It is unknown when Antarctica was first discovered. The ancient Greek geographer and astronomer Hipparchus and others hypothesized of the existence of a southern continent somewhere at the South Pole. Modern cartographers, including Harvard professor Charles H. Hapgood in Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings (1966), have used ancient and medieval maps in an attempt to prove that someone in antiquity had accurately mapped the large land mass.

We began to learn more about the topography and fossilized plant and animal life in Antarctica after explorers visited in the 19th and 20th centuries. There is a book in HSP’s collection titled Antarctica, published in Philadelphia in 1902 and written by Edwin Swift Balch, a Harvard-educated Philadelphia lawyer and prolific writer. This seminal volume includes an interesting map of Palmer Peninsula (pictured below). This peninsula, formally known now as the Antarctic Peninsula, was discovered by Nathaniel Palmer (1799-1877) of Connecticut in November 1820 during his sealing ventures. Later many fossilized or extinct animal species were found in this area, particularly upon Seymour Island in the Weddell Sea, one of the largest ice-free areas in all of Antarctica.

Also found in the book is an account of a mysterious discovery made by Norwegian whaler Capt. Carl Anton Larsen. While on the ship, the Jason, on November 18, 1893, Larsen reported finding “balls made of sand and cement, resting on pillars” on Seymour Island. “We collected some fifty of them, and they had the appearance of having been made by man’s hand,” Larsen wrote. Despite Larsen’s account, conventional science ridicules the idea of ancient visitors to the South Pole.

HSP also holds an image of Lt. Charles Wilkes of New York City. Wilkes is well known primarily for his involvement during the Civil War in the Trent Affair of 1861, but Wilkes (pictured below, right) is also known for leading the “United States Exploring Expedition,” or the “Wilkes Expedition” with five vessels. He left Hampton Roads, Virginia, with great fanfare in July of 1838, and arrived in Antarctica in December of 1839. Pictured below is a letter written by Lewis Warrington to Lt. Wilkes, dated July 23, 1838, in which Warrington refers to the upcoming expedition.

One of the first individuals to traverse parts of the southern continent by air was Navy Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd of Virginia, who traveled there as early as 1929. During his fourth and final expedition to the frigid South, Byrd sent a telegram (pictured below)dated February 7, 1947, to a John B. Givin, sending “warmest greetings from the coldest place” and asking if he’d like “to stake out a claim … at the bottom of the world.”

Like so many other individuals, topics, or subjects in history, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania is a storehouse of information, not restricted to Pennsylvania’s past alone. Explorers and their discoveries at the South Pole or that mysterious continent we call Antarctica, is certainly no exception to this rule.

***

During the middle of the summer heat, we thought we’d focus on one of the coldest places on earth—the continent of Antarctica. It is unknown when Antarctica was first discovered. The ancient Greek geographer and astronomer Hipparchus and others hypothesized of the existence of a southern continent somewhere at the South Pole. Modern cartographers, including Harvard professor Charles H. Hapgood in Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings (1966), have used ancient and medieval maps in an attempt to prove that someone in antiquity had accurately mapped the large land mass.

We began to learn more about the topography and fossilized plant and animal life in Antarctica after explorers visited in the 19th and 20th centuries. There is a book in HSP’s collection titled Antarctica, published in Philadelphia in 1902 and written by Edwin Swift Balch, a Harvard-educated Philadelphia lawyer and prolific writer. This seminal volume includes an interesting map of Palmer Peninsula (pictured below). This peninsula, formally known now as the Antarctic Peninsula, was discovered by Nathaniel Palmer (1799-1877) of Connecticut in November 1820 during his sealing ventures. Later many fossilized or extinct animal species were found in this area, particularly upon Seymour Island in the Weddell Sea, one of the largest ice-free areas in all of Antarctica.

|

| PALMER PENINSULA from the Edwin Swift BALCH BOOK |

HSP also holds an image of Lt. Charles Wilkes of New York City. Wilkes is well known primarily for his involvement during the Civil War in the Trent Affair of 1861, but Wilkes (pictured below, right) is also known for leading the “United States Exploring Expedition,” or the “Wilkes Expedition” with five vessels. He left Hampton Roads, Virginia, with great fanfare in July of 1838, and arrived in Antarctica in December of 1839. Pictured below is a letter written by Lewis Warrington to Lt. Wilkes, dated July 23, 1838, in which Warrington refers to the upcoming expedition.

|

| Letter of Lewis Warrington to Charles Wilkes, July 23, 1838 |

|

| Charles Wilkes |

One of the first individuals to traverse parts of the southern continent by air was Navy Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd of Virginia, who traveled there as early as 1929. During his fourth and final expedition to the frigid South, Byrd sent a telegram (pictured below)dated February 7, 1947, to a John B. Givin, sending “warmest greetings from the coldest place” and asking if he’d like “to stake out a claim … at the bottom of the world.”

|

| TELEGRAM of DICK BYRD TO JOHN B. GIVIN |

Monday, August 16, 2010

The Lost World of Antarctica

Recently, within my other publication here at the Society, History Hits (which may be obtained free by subscription here), I wrote a short article with graphics entitled, "Antarctica: The Lost Continent." Writings of famed Antarctic explorers such as Charles Wilkes, Admiral Richard E. Byrd, etc., can be found here within the Society's collections, which has prompted me to give some additional background information to the above article for this Blog, plus add a few things not included in those remarks, information largely unknown to the public.

Many years ago, while residing in the West, I came across a work about the 'frozen wilderness' of Antarctica entitled, Antarctica: The Worst Place in the World, (1966), by Allyn Baum. The author gives an account from the journal of Captain Carl Anton Larsen, who in November of 1893, in the ship Jason, made anchor off Seymour Island, located on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.

For years now, many fossils of ancient life have been discovered in this remote area, as well as within the 'dry valleys' on the continent itself, from dinosaur remains to ancient botanical specimens, showing how at one time the area was tropical in climate. Purportedly however, no human remains have ever been discovered. Yet according to Baum, Capt. Larsen specifically makes mention of the discovery of some "fifty balls set on pillars...these (balls of clay) had every appearance of having been made by human hands."

One can imagine if the above is true, it would be one of the most important scientific discoveries, since according to conventional theory, the present ice-sheet blanketing the Antarctic continent has existed for millions of years. Naturally I wanted the source for such a statement, though Baum failed to give one. Writing to the author, he stated he'd lost the reference. Thus, began a search that covered many years, in my attempt to locate the original or primary source for this provocative and mysterious statement.

In university libraries from California, to Utah, to Kentucky and on to Pennsylvania, I examined multiple volumes and numerous publications concerning the Antarctic, but nothing contained any data relative to the aforementioned discovery by Capt. Larsen. Twenty-five years ago however, when I first became employed here at 'The Historical Society of Pennsylvania,' and 'on a whim,' I checked the card catalog of the Library, and surprisingly found one volume actually on Antarctica, by Philadelphia lawyer and writer, Thomas Willing Balch, entitled simply, Antarctica, published in Philadelphia in 1902, a seminal volume on early Antarctic exploration, which actually included Larsen's discovery in 1893. Quoting from his diary or journal, Larsen remarked how on Saturday, November 18th, at Cape Seymour, they found petrified wood and worms, while,

"At other places we found balls formed of sand and cement which lay upon pillars of the same kind. We collected in several places some fifty of them; they had the appearance of having been made by the hand of man."

The above work then in turn, gave as its source, the famed Geographical Journal, No.4, Vol.IV., for October, 1894, a published article entitled, "The Voyage of the "Jason" to the Antarctic Regions," being an 'Abstract of Journal kept by Capt. C. A. Larsen,' on pp's. 333-344, which quotes once again, Larsen on p.333, who states how, "At other places we saw balls of sand and cement resting upon pillars composed of the same constituents. We collected some fifty of them, and they had the appearance of having been made by man's hand."

Dr. Charles W. Donald, also observed the above "pillars," during his visit to Seymour Island on the ship, the Active, part of the Scottish Dundee Whaling Fishing Company, which was in Antarctic waters at approximately the same time as Capt. Larsen of the Jason, stating his belief that the "balls formed of sand and cement" were actually "columns of basalt which had crumbled into concentric scaled balls."

Regardless, since the late 19th century, Chilean archaeologists have reportedly found 'arrowheads' at Antarctica on King George Island of the South Shetland Islands, believed to have been left there by voyagers from the South American continent. Also, Charles H. Hapgood, the late Harvard cartographer who attempted to show in his famous work, Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings (1966), that Antarctica was mapped centuries ago by some ancient maritime civilization, as revealed by the famed Piri Reis Map found in Turkey and dated to 1513, as well as certain other maps of Medieval vintage, based perhaps in turn on ancient Greek or Phoenecian works (see for example, "New Analysis Hints Ancient Explorers Mapped Antarctic," New York Times, September 25th, 1984, p.C-2).

The point is that much remains to be discovered on the great South Polar continent, but also in often neglected historical repositories like 'The Historical Society of Pennsylvania' in Philadelphia. Thus one simply has to be patient, curious and inquisitive enough, if you are ever going to truly find, the Hidden Histories,' that are 'out there,' or here, simply waiting to be discovered.

Many years ago, while residing in the West, I came across a work about the 'frozen wilderness' of Antarctica entitled, Antarctica: The Worst Place in the World, (1966), by Allyn Baum. The author gives an account from the journal of Captain Carl Anton Larsen, who in November of 1893, in the ship Jason, made anchor off Seymour Island, located on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.